Unholy Influence: The Exorcist, the Spirits, and the Rituals of Banishment Across Cultures

A haunted book, a restless bookstore, and what exorcism reveals about our deepest fears—across faiths, history, and the veil between worlds.

By Matthew D. Jackson | PARAHOLICS | October 2025

It wasn’t just any book that fell.

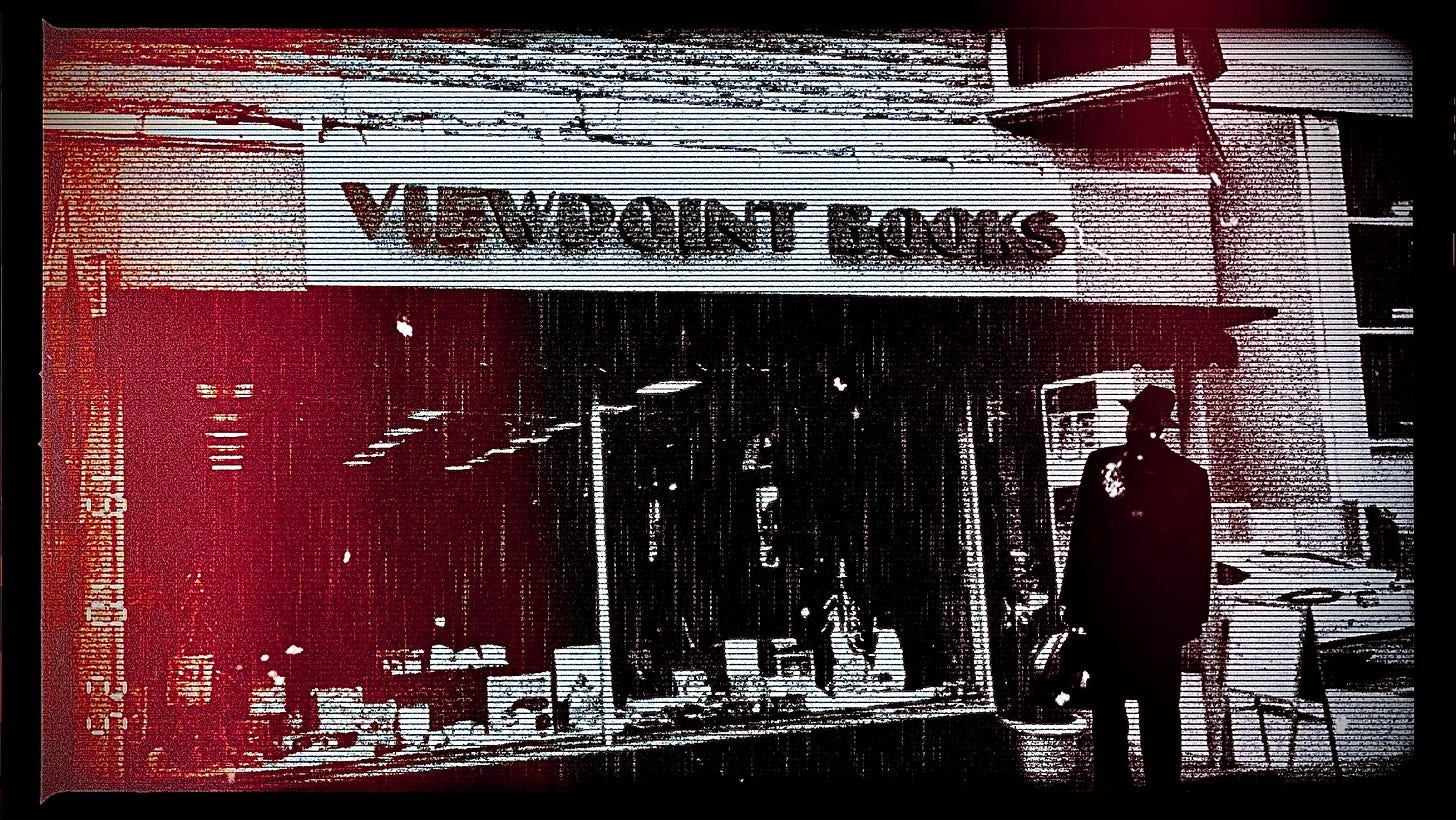

It was The Exorcist—facedown, off the display shelf at Viewpoint Books—the beloved indie bookstore in Columbus, Indiana. And it didn’t fall quietly. The book launched itself just at the edge of her vision—but clearly enough to catch both the attention of her and an employee standing at the register nearby. The moment was strange enough that Beth Stroh, the bookstore’s owner, messaged me immediately. Her text led to another full-blown paranormal investigation of the shop.

Watch the Investigation: The Exorcist Incident at Viewpoint Books!

A coincidence? Maybe. But that’s never quite how it feels when it’s that book.

What followed was a series of events that seemed to flirt with something deeper than residual energy: a strange timing, a provocative gesture, and a communication session where intelligent voices—through a method known as Instrumental Trans-Communication (ITC)—responded to our questions with uncanny precision. One voice, when asked why the book had been knocked down, replied:

“Dirty book.”

Another? “Bowdern.”

It’s a name you rarely hear—unless you’ve studied Father William Bowdern, the Jesuit priest who led the real-life exorcisms that inspired The Exorcist.

The book’s fall, the ITC responses, and the quiet current running through the bookstore’s basement all seemed to converge on not just a haunting—it felt like an answer shaped by awareness.

But rather than letting this strange encounter be reduced to a spooky story, let’s widen the lens. Exorcism is one of humanity’s oldest rituals. It’s been a source of mystery, power, and fear across cultures for thousands of years. Catholicism may have codified the rite, but the impulse to drive out unwanted forces—whether spirits, demons, or madness—is far older and far more universal.

So this isn’t just about a book. Or even a ghost. It’s about what happens when we try to name, fight, and understand the forces we can’t see—those that exist just beyond the veil of ordinary perception. And what it might mean when they talk back.

The Modern Obsession with Possession

Despite being rooted in ancient ritual, the concept of possession has never been more alive in popular culture. Films like The Exorcist (1973) didn’t just terrify a generation—they redefined how the Western world imagines spiritual intrusion. They gave evil a voice, a face, and a cinematic vocabulary: spinning heads, guttural growls, bodies flung by invisible hands.

But long before Regan MacNeil crawled backward down a staircase, the idea that a spirit could inhabit a body—take over the mind, bend the will—was embedded deep in the global human story. The difference now is the frame.

Possession has become entertainment.

We binge demonic thrillers and share “possessed girl on the subway” clips on social media. Exorcism is a meme, a genre, a punchline. Paranormal TV shows dangle it as the final boss—proof that a location has crossed from spooky to serious. Even some ghost hunters now stage dramatic confrontations that resemble low-budget reenactments of The Rite.

But what’s often missing in this spectacle is nuance. The idea that possession might be symbolic, psychological, or culturally specific is often ignored in favor of fear-mongering. And worse, the rise of this obsession often sidelines the voices of those who live in spiritual traditions where spirit influence is real—but not always sinister.

There’s a hunger in our culture to believe in demons—just as much as there’s a hunger to mock the idea. And maybe that’s because the idea of being overtaken speaks to something primal. Something unspoken in our age of overstimulation, fractured attention, and identity crisis.

Possession, in this modern context, isn’t just about ghosts.

It’s about what owns us.

The Catholic Rite and Its Roots

If possession is the wound, then exorcism is the attempted cure—or, at least, the ritual intervention. And in the West, no tradition has shaped our collective imagination of exorcism more than the Catholic Church.

The Roman Catholic rite of exorcism isn’t medieval pageantry or Hollywood spectacle. It’s a carefully delineated process—codified, updated, and tightly controlled. First formalized in the Rituale Romanum of 1614, the Church’s rite requires strict discernment before any ceremony is approved. Mental illness must be ruled out. Psychological evaluations are expected. And even then, only specially trained priests, operating with explicit episcopal permission, are authorized to perform the rite. (While cultural traditions view possession spiritually, modern medicine often interprets similar symptoms as mental health conditions—consult professionals accordingly.)

In the 20th century, very few Catholic exorcisms were publicly acknowledged—until the case of Robbie Mannheim (a pseudonym for Ronald Edwin Hunkeler) captured the attention of Jesuit circles in the late 1940s (Allen, 2021). His alleged possession and subsequent exorcisms at the hands of Father William Bowdern in St. Louis became the seed for William Peter Blatty’s novel The Exorcist (Blatty, 2011).

Ironically, the Church never intended for this case to be publicized. Father Bowdern and his assistants kept extensive notes, but the records were sealed. Blatty learned of the case years later through academic sources and clergy contacts—not official disclosure.

The Catholic Church walks a strange line. On one hand, it’s cautious to avoid fueling hysteria or validating superstition. On the other, it continues to appoint exorcists around the world, acknowledging that spiritual affliction can be real—and that evil, however we define it, sometimes requires confrontation.

But even here, within one of the most rigid institutions in human history, the definition of possession is far from settled. Is the exorcist battling a literal demon? A manifestation of trauma? A psychosomatic archetype? Or some mix of all three?

The ritual may be standardized. The mystery remains.

Global Rites of Expulsion

The Catholic rite of exorcism, while widely known in the West, is but one thread in a vast global network of traditions that seek to restore spiritual and energetic balance when it is believed to be disrupted. Nearly every culture has developed its own form of spiritual intervention—some dramatic and theatrical, others contemplative and symbolic.

In Islam, ruqyah is recited from the Qur’an to drive out harmful spirits (jinn), often accompanied by physical rituals like blowing or anointing with oil. In Judaism, dybbuk possession is countered through prayers of atonement and sacred naming, occasionally led by a rabbi in structured exorcisms. Hinduism offers manifold paths, from chanting Vedic mantras and invoking deities to specific rites found in the Atharva Veda designed to ward off malign influences (Goodman, 1988).

In African Traditional Religions, particularly among the Yoruba or Bantu peoples, spirit possession is more nuanced—sometimes seen as healing or divinatory, other times as intrusion. Ritual drumming, dance, and invocation are used to restore communal harmony. Likewise, in Vodou and Santería, trance states and possession by loa or orishas are common, but when unwanted spirits arrive, practitioners may employ baths, offerings, and the assistance of powerful intermediaries.

Tibetan Buddhism, though not centered around the concept of demonic possession, acknowledges spiritual interference as part of samsaric suffering. Rather than confronting “evil” head-on, practitioners may engage in rituals such as chod, which invites the practitioner to visualize offering their own body to hungry spirits as a radical act of compassion, or phowa, which guides consciousness at the moment of death. Protective mantras, mudras, and wrathful deity visualizations—like those of Mahakala or Vajrakilaya—are also employed to transmute negative energies rather than expel them violently (Levack, 2013).

These traditions vary widely in tone and cosmology—some depicting spiritual affliction as a moral failing, others as imbalance, ancestral unrest, or a call for attention. What unites them is the impulse to rebalance, to reassert connection between body, spirit, and cosmos, and to do so through a framework deeply embedded in the culture’s view of reality.

Exorcism as Mirror

What if the point of exorcism isn’t just to remove something foreign, but to reveal something hidden? Across faiths and cultures, these rituals often act less like forceful expulsions and more like mirrors—showing us our own shadows, our fears, our projections.

The possessed often become symbols of whatever a society fears most: sexuality, madness, heresy, rebellion, or grief that cannot be metabolized. In this light, the body becomes a stage upon which cultural anxiety plays out. In the West, especially post-Enlightenment, possession is frequently cast as a rare spiritual siege—one that justifies spectacle and secrecy alike. But in other traditions, spirit interaction is not always pathology. It may be communication. It may be calling (Ferber, 2004).

Viewed through this lens, exorcism becomes less about domination and more about discernment. Who gets labeled “possessed,” and by whose authority? Who decides when a voice is sacred or sick? The more we ask these questions, the less tidy the answers become.

We might ask whether exorcisms sometimes serve the ego more than the soul—allowing the practitioner to step into a savior role, or the witnesses to rehearse their belief in evil. The act of driving something out becomes performance: a reaffirmation of the order we think we understand, and the borders we’re terrified to see breached (Turner, 1969).

But if possession is sometimes performance, then so is expulsion. And if spirit communication challenges the boundaries of belief, then so does the act of naming what’s speaking through us.

Instrumental Trans-Communication and the Possibility of Commentary

The incident at Viewpoint Books became more than a quirky haunting the moment we turned to Instrumental Trans-Communication (ITC) to explore it further. As we asked questions about the book incident, we received responses that pointed directly to historical figures and deeper themes tied to the real-life exorcism case that inspired The Exorcist—offering what felt less like ambient echoes and more like intelligent commentary (Macy, 1999).

Among the names to come through was “Bowdern”—a direct reference to Father William Bowdern, the Jesuit priest who led the 1949 exorcism in St.Louis. This wasn’t a name we had mentioned aloud. It surfaced during our ITC session as if the spirits—or “the Others,” as some researchers call them—wanted to highlight their awareness of the story, or their involvement in shaping how it unfolds in human memory.

Another response simply said: “We’re not vicious.” Was this a defense from those responsible for knocking the book off its display? A reminder that not all uninvited presences are malevolent? Or was it commentary on the legacy of The Exorcist itself—a narrative that framed all spirit contact as dark, violent, or demonic?

The clarity of these responses—Bowdern, Robbie, Father Williams—makes it hard to ignore the historical trail they seem to be tracing. But what if these weren’t just acknowledgments? I’ve started to wonder whether they were corrections—a pointed rejection of the dramatized narrative. As if the voices were pushing back on the spectacle. That book, that film, this mythos—it may have made people millions, but maybe to them, it cheapened something sacred or exploited real suffering. Maybe what we heard wasn’t fascination. Maybe it was a quiet protest.

Then came a stranger phrase: “Performing angels.” Was this a veiled reference to theological debates—that so-called angels might be deceivers in disguise, performing roles to influence belief or test faith? Or was it reassurance that protective forces were present and active during our questioning, acting as benevolent performers in a cosmic drama (Rose, 1962)?

Whatever these replies meant, they spoke in riddles. But like any good riddle, their power came not just from what they said—but what they made us consider. The dialogue didn’t offer proof or closure. It offered reflection. Engagement. A nudge to look closer.

And in a way, that’s what ITC at its best has always done. It’s not just about catching a voice. It’s about being willing to listen.

Echoes, Not Answers

Exorcism, whether practiced in a cathedral, a village hut, or the back room of a bookstore, is never just about spirits. It’s about people. About how we process trauma. About how we assign meaning to suffering. And sometimes, it’s about how we tell stories to keep ourselves from being afraid of the dark (Radin, 2018).

The events at Viewpoint Books—fleeting, unexplained, but real—didn’t affirm or debunk any belief system. They simply happened. The book fell. The names came through. The responses stirred something ancient.

Through the lens of ITC, we glimpsed not just what might linger beyond the veil, but how those presences may respond to what we bring into a space: fear, curiosity, reverence, or cynicism. And perhaps more importantly, we saw how we respond when the unknown stirs back.

Whether the voices we heard were memory, mischief, or manifestation, they acted as guides—pointing not just to Bowdern or Robbie, but to our ongoing human fascination with evil, salvation, and the blurred threshold between (Zimdars-Swartz, 1991).

The Others may speak in riddles. But maybe that’s the point. They don’t hand us truth. They invite us to participate in its uncovering.

So when a book crashes to the floor, when a voice says, “We’re not vicious,” when an unseen whisper names the priest who once battled darkness with prayer and persistence—

It’s not just a haunting.

It’s a conversation.

Postscript

If you’re interested in the true story that inspired The Exorcist, I highly recommend The Devil Came to St. Louis: 2025 Uncensored Edition by Troy Taylor. This updated release includes previously unpublished material, new interviews, and a closer look at the life of Ronald Edwin Hunkeler—the real “Robbie.”

You can order it directly from the publisher via American Hauntings Ink.

But if possible, consider ordering it through Viewpoint Books in Columbus, Indiana—the very place where the book fell, and the veil seemed to ripple.